Reflections on Time, Presence, and Memory: A Literary Parallel Between Fiction and Reality

Education

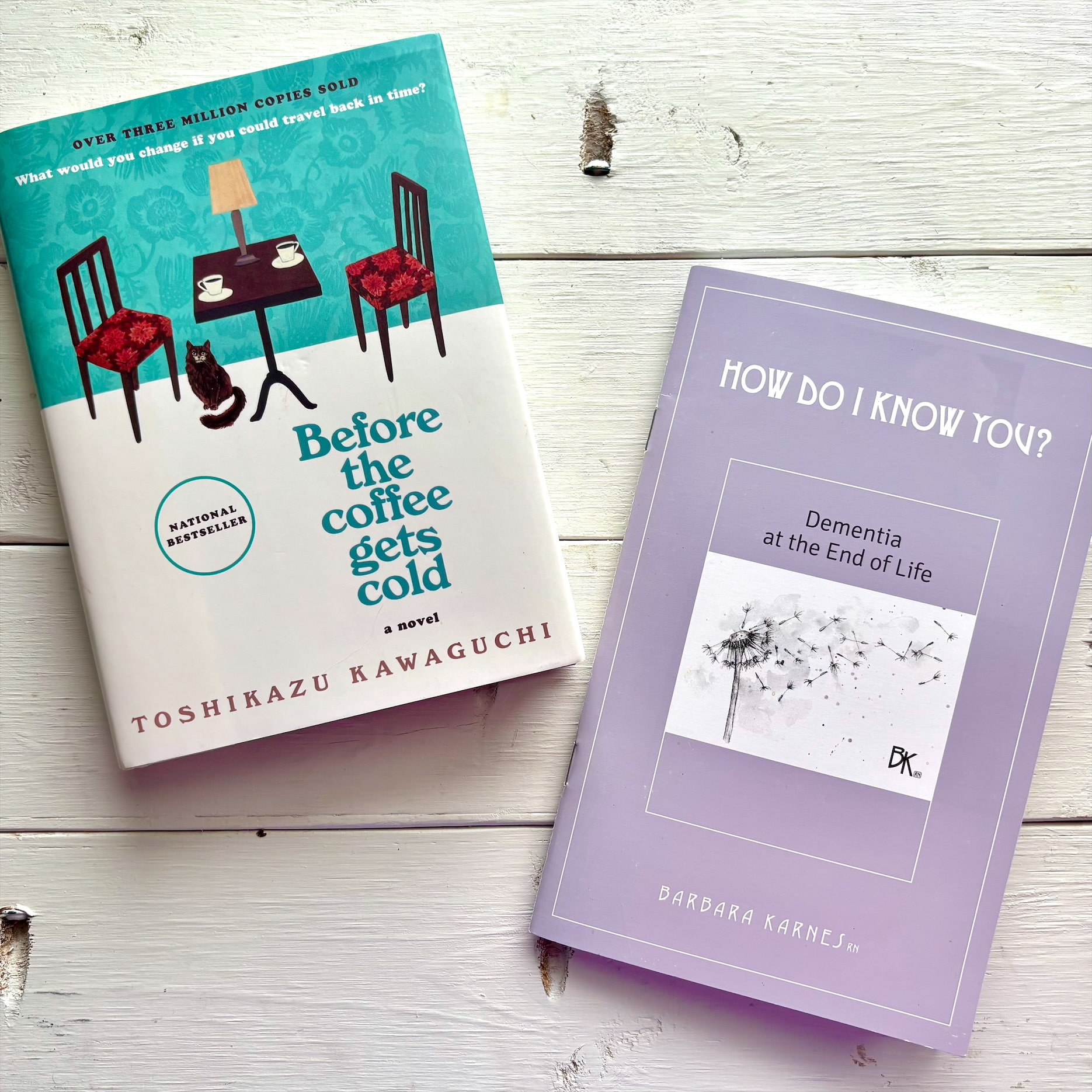

In hospice care, where the boundary between presence and absence often blurs, stories can offer unexpected clarity. “Before the Coffee Gets Cold” by Toshikazu Kawaguchi and “How Do I know You?” by Barbara Karnes, RN, are two such works that, though vastly different in style and genre, converge around central themes of memory, grief, and the human longing for connection.

Kawaguchi’s novel, set in a quaint Tokyo café, revolves around a fantastical premise: patrons can travel back in time, but only within the confines of the café, and only for the duration it takes for their coffee to cool. The characters in the story use this limited window to seek closure, rekindle lost bonds, or express unspoken emotions in their individual lives. Despite the magical setup, the novel is grounded in emotional realism: it does not promise to change the future, only to offer a deeper understanding of the past.

Conversely, Karnes’ work is rooted in clinical experience and compassion as she herself is a nurse and end-of-life educator. “How Do I know You?” addresses the progression of dementia and the shifting ways in which loved ones can better understand individuals undergoing cognitive decline. With clarity and grace, Karnes outlines how traditional forms of communication give way to non-verbal cues, emotional presence, and touch. Even when our loved ones no longer recognize us, even when conversation is no longer possible, our presence still speaks. A quiet moment. A hand held. A familiar voice in the room. These are gifts that do not rely on memory. They are felt, not remembered. The book challenges caregivers to move beyond the need for recognition or conversation and instead value the unspoken: being with a loved one in copresence, rather than doing something for them.

While one book offers metaphorical time travel and the other a grounded clinical guide, both explore the same existential terrain: how do we remain connected when time, memory, or recognition fails us?

In hospice care, this question is especially resonant. As diseases advance, patients may lose memories of names, faces, and relationships. Moments of clarity may grow increasingly rare. Yet, as Karnes reminds us, the emotional self often endures, and the need for comfort, familiarity, and love remains. Likewise, in Kawaguchi’s café, the characters often come to realize that the act of showing up—of simply being present—is more meaningful than any words spoken or time reclaimed. This theme is especially poignant in Kohtake’s story, where her husband Fusagi’s dementia gradually erases his memory of her as his wife, even as her devotion to him never wavers.

These works jointly highlight that meaningful connection does not always rely on memory or dialogue. In fact, some of the most profound moments come in silence, in shared space, or in a final touch of the hand. For those working in hospice or caring for loved ones with dementia, both books serve as a reminder that love is not always linear, nor is closure always verbal. Sometimes, presence itself is the most powerful form of communication.

Written by: V Perera